Chronic conditions are literally killing us.

They impact nearly half of the U.S. population and roughly a third of those people have more than one chronic condition. The cost of these conditions eats up 84% of the healthcare spend in America.

Much attention is given to the most well-known chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes. But chronic conditions also encompass over 100 autoimmune issues, affecting over 23 million people (as of 2017).

Worse, patients with chronic conditions see an average of seven doctors. Which gets at the heart of the problem.

Those doctors are most likely not all in the same healthcare system and not coordinating with one another. In a healthcare system that prioritizes and compensates prescriptions and testing with doctors reacting to isolated symptoms or concerns, patients are often left to fill scrips, wait for test results, and plan regular returns to multiple offices.

Chronic conditions patients have learned the hard way that we must be engaged partners in our healthcare. That often means serving as both documentarian – cataloging our litany of issues – and advocate – briefing and coordinating among each new physician – at the same time.

I say “our” because I am a chronic condition patient. This has been my experience for going on three decades now. It is ultimately what led me to start my third entrepreneurial venture – Journal My Health, using my background in the technology field to solve for a very personal problem.

In our recent webinar, panelist Dr. Joanne Kakaty-Monzo said that we know how women with chronic conditions are treated by the medical establishment when they seek help. She observed that many times they are not heard or believed, or there is a tendency to dismiss their many symptoms as a mental health diagnosis.

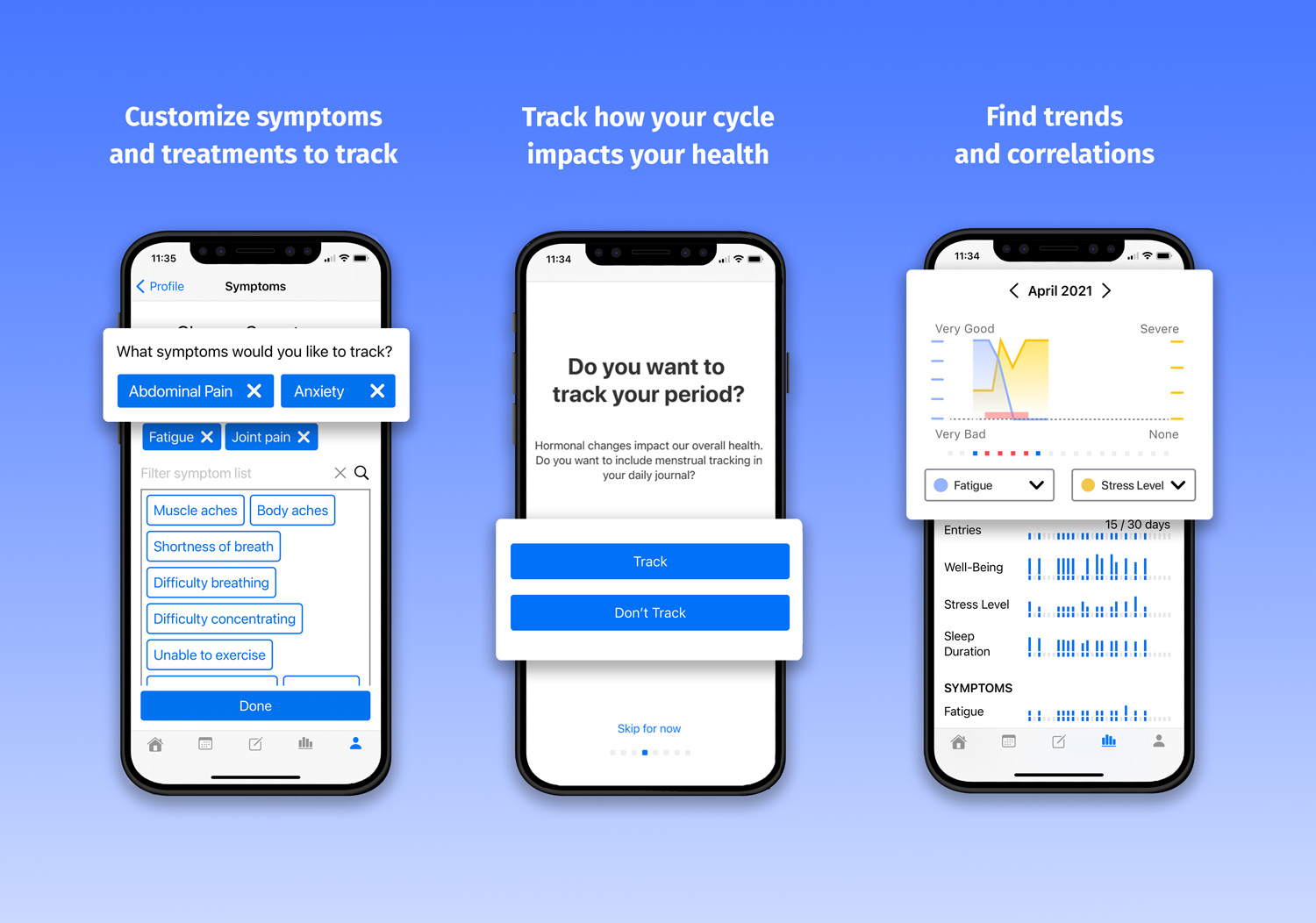

The idea is to make it as easy as possible for someone who has a chronic condition to capture daily information about their symptoms and other items, then combine it with other data existing on a smartphone or wearable. It produces custom reporting based on individual experiences that empowers us as the central agents in our respective healthcare journeys.

But the types of data we capture are critical. And for too long, traditional healthcare has ignored one vital piece of data that may hold the secret to chronic conditions for millions of people.

In my research around chronic conditions, I was surprised to learn that 80% of the 23 million people with chronic autoimmune issues – lupus, arthritis, IBS, etc. – are women. There is scant research being done on why there is such a prevalence of these conditions in women. There is also little research on how women’s physiological makeup impacts the symptoms and treatments for these conditions.

But in our recent webinar “The Unexplained Intersection of Women’s Health and Chronic Conditions”, panelist Dr. Joanne Kakaty-Monzo did say we know how women with these conditions are often treated by the medical establishment when they seek help. She observed that many times they are not heard or believed or there is a tendency to dismiss their many symptoms as a mental health diagnosis.

Remind anyone of early diagnoses and treatments of women for hysteria?

This became a personal mission for me. As a woman with a chronic condition committed to building a better way for patients to navigate our health system, I want to understand what types of data could help track and resolve our issues.

That’s why beginning on March 15th, 2022, Journal My Health will launch a period tracker for female patients. Current period tracking is largely about predicting when your period will happen for purposes of fertility or sexual health. But we want to understand if a women’s menstrual cycle – its frequency, duration, even when it ends at menopause – has implications for chronic conditions.

If such a large portion of chronic condition patients are women, then periods are one of their fundamental commonalities. We need to consider it as a relational data point when evaluating the severity and types of our condition’s symptoms, the success of treatments, and the appropriateness of medications.

This will take time and might prove unreliable, but at the very least we hope to jumpstart a deeper conversation about the different experience of women versus men in medicine – and how and why the medical community should be listening.